DALIA AL-DUJAILI

The newly-released book, Yesterday, Come Closer, is an urgent attempt at consolidating Palestinian art, music, and writing in the face of genocide.

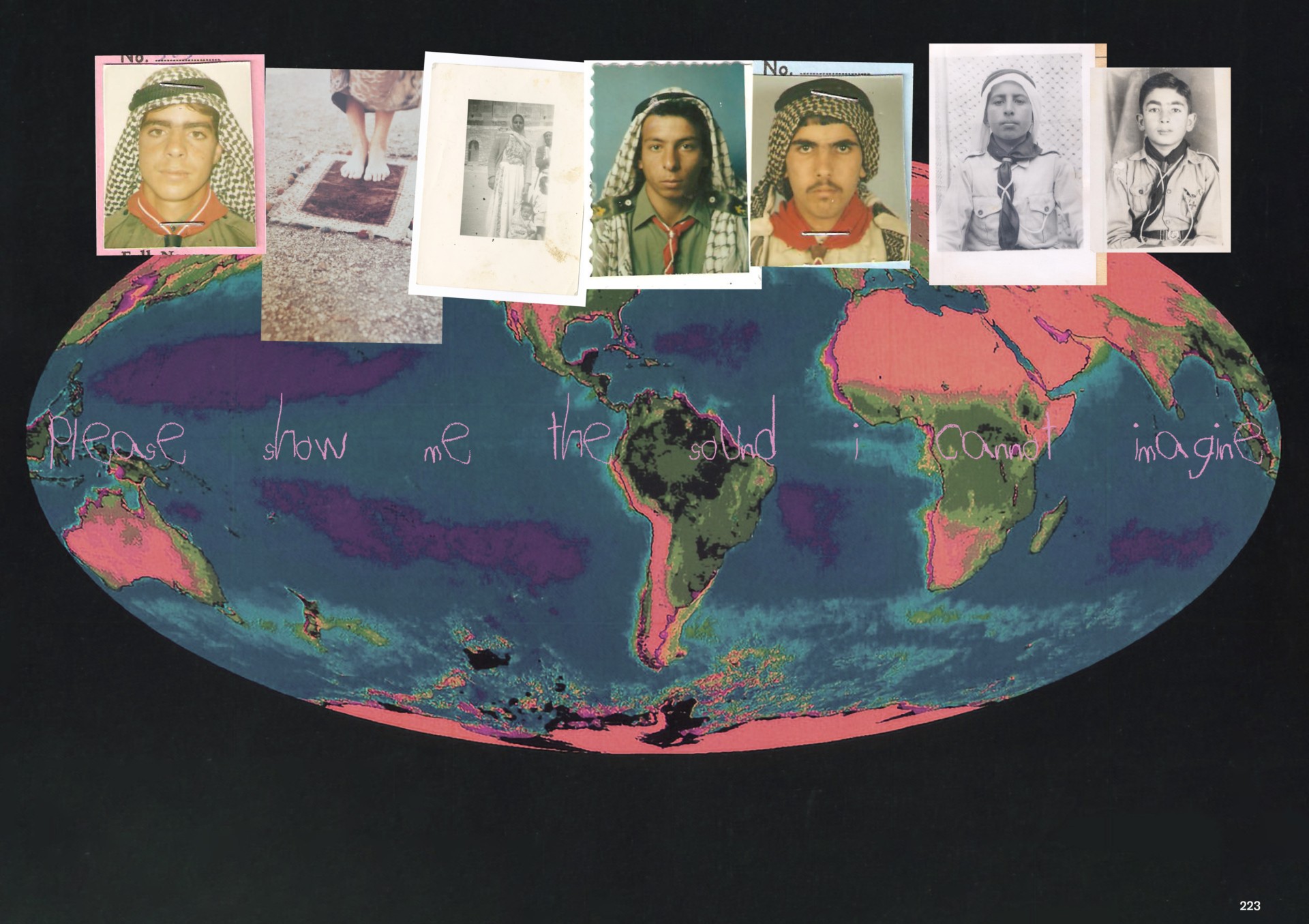

Created by visual artist Ibrahem Hasan with contributions from practitioners and thinkers who have contributed to various resistance movements throughout history, Yesterday, Come Closer is an attempt at consolidating Palestinian collective memory as the violent untethering of Indigenous people from their land and ecosystems relentlessly continues in Gaza and the West Bank. The book is an urgent exploration of all facets of Palestinian liberation movements, spanning works that reflect on the necessary role of women to the resistance, the transformative importance of religion and spirituality, as well as the present-day violence of eco-colonialism and land degradation. All profits from the book are being donated to grassroots organizations and efforts on the ground in Palestine.

After designing the book for an exhibition last year, Hasan decided to “rip [it] apart” and start over—this time enlisting the help of London-based writer Sarra Alayyan who joined the project as lead narrative editor and researcher alongside assistant narrative editor Hussein Amri, calligrapher Tarin Karimbux, researcher Moun Aicha Soussan and film researcher Jude Khalili. “I realized in the making of that [exhibition that] I didn’t really know what the hell I was making or doing,” Hasan told Atmos. “It was just a series of questions and I was figuring out [the end goal]. I realized that I needed to do more digging, I needed to do more understanding of who I am. And then October 7 [happened], and all of us as a team knew that we needed a timeout for all the emotion. [That was when] there was a recalibration [of the project].”

“As I was making the book I knew that it was going to be a therapeutic process. It was built around the visualization of the memories that I had from childhood to adulthood as a Palestinian American trying to understand and conceptualize the idea of home.”

CREATOR OF YESTERDAY, COME CLOSER

It’s a sentiment that is shared with Hasan’s wider team. “A lot of memory studies went into the research,” said Alayyan. “This is a very mnemonic book that looks at how one person can bridge a personal memory [of home] with the collective memory of Palestine.” Memory is a recurring theme throughout Yesterday, Come Closer in part because it is so crucial to the wider Palestinian struggle for liberation. After all, the erasure of memory ensures the erasure of the subject itself––and it’s why the title, Yesterday, Come Closer, is positioned as an imperative phrase that’s begging for greater intimacy and proximity with history.

The book also creates space for envisioning a new future, one that promises liberation in part by remembering Palestinian history and the Palestinian people’s struggle against apartheid and state-sanctioned violence. Sophia Azeb’s written essay “Who Will We Be When We Are Free?” is a powerful meditation on identity and Palestinian futurity.

Yesterday, Come Closer makes manifest the memories of the Palestinian collective experience both in the diaspora and at home through archival images of Indigenous Palestinian women picking olives from trees, adorned with traditional brass and silver pendants, amulets and chain necklaces dressed in beautiful dresses woven with tatreez. These images not only remind us of the historic and sacred presence of Palestinian people on the land, but serve to highlight a darker reality in which life is becoming increasingly difficult to sustain––years before October 7th. For decades, the Israeli military has forbidden Palestinians to fish, limited their agricultural work, forbidden them to harvest their crops, bombarded their soil with poisonous gasses, and killed their livestock amid countless more abuses.

Yesterday, Come Closer was published alongside a Sound System created in collaboration with Ramallah-based Yesterday, Come Closer producer Ahmed Zaghmouri and Palestinian platform Radio Al-Hara, which lives on both the website and independently . Contributors are free to submit their own audio, which so far includes interviews and conversations between Palestinians as well as (in Zaghmouri’s words) “the deadliest techno mix ever” by Kuwait-based artist Van Boom, traditional folkloric music, an eerie performance by “Gaza Children’s Space Ensemble,” Quran recitation, and much more. The end result is a digitally-transmittable, borderless, and accessible sound system, intentionally collecting community voices for people “that maybe don’t have the words to describe what they feel,” said Zaghmouri.

The Yesterday, Come Closer sound system is a vital component of the project’s liberatory motivations. “It’s the first time that anyone’s [been] allowed to do whatever [they want],” Zaghmouri said, speaking of the soundsystem. “I’d rather listen to what someone feels musically rather than read books about how people think Palestine should or should not be… The most glorified photographers that take pictures of Palestine are white people on a visit.”

These images not only remind us of the historic and sacred presence of Palestinian people on the land but serve to highlight a darker reality in which life is becoming increasingly difficult to sustain—years before October 7th.

“I’m truly trying to do the best I can to support my people and my bloodline; my ancestors,” said Hasan. The goal was to create a book which was fully comprehensive and accurate to the Palestinian experience, and that meant letting go of academia and statistics—and allowing emotion to flow through the pages. It’s a spirit that’s reflected throughout the book; like in Adam Rouhana’s photograph of a boy joyfully eating a cracked watermelon or in the spontaneous, diary-like annotations with no clearly attributed author.

Yesterday, Come Closer is a devotional work: one which will surely go down as a testament to the Palestinian spirit of endurance and the palpable power of a community’s creative collaboration; one that will continue to honor the ancestral voices who maintain today’s spirit of resistance to the ongoing violent occupation of land and its people. In the words of contributing writer Karmel Sabri: “Without the land and the literal fruits of our love and labor, what is this all for? She deserves to be respected and tended to by the people who understand her best.”

Source: www.atmos.earth

Arabgazette Arabgazette Magazine

Arabgazette Arabgazette Magazine